Electrophoretic component of electric pulses determines the efficacy of in vivo DNA electro

HUMAN GENE THERAPY 16:1194–1201 (October 2005)

?Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

Electrophoretic Component of Electric Pulses Determines the Efficacy of In Vivo DNA Electrotransfer SAULIUS S?ATKAUSKAS,1,2FRANCK ANDRé,1MICHEL F. BUREAU,3DANIEL SCHERMAN,3

DAMIJAN MIKLAVCˇICˇ,4and LLUIS M. MIR1

ABSTRACT

Efficient DNA electrotransfer can be achieved with combinations of short high-voltage (HV) and long low-voltage (LV) pulses that cover two effects of the pulses, namely, target cell electropermeabilization and DNA electrophoresis within the tissue. Because HV and LV can be delivered with a lag up to 3000 sec between them, we considered that it was possible to analyze separately the respective importance of the two types of effects of the electric fields on DNA electrotransfer efficiency. The tibialis cranialis muscles of C57BL/6 mice were injected with plasmid DNA encoding luciferase or green fluorescent protein and then exposed to vari-ous combinations of HV and LV pulses. DNA electrotransfer efficacy was determined by measuring lucifer-ase activity in the treated muscles. We found that for effective DNA electrotransfer into skeletal muscles the HV pulse is prerequisite; however, its number and duration do not significantly affect electrotransfer effi-cacy. DNA electrotransfer efficacy is dependent mainly on the parameters of the LV pulse(s). We report that different LV number, LV individual duration, and LV strength can be used, provided the total duration and field strength result in convenient electrophoretic transport of DN A toward and/or across a permeabilized membrane.

INTRODUCTION

E LECTRICALLY MEDIATED GENE TRANSFER, also termed DNA

electrotransfer or electrogene therapy, has gained real in-terest as it is one of the most effective methods of in vivo non-viral gene transfer (André and Mir, 2004). The method has been shown to be effective in electrotransferring plasmid DNA to various tissues: muscles (Aihara and Miyazaki, 1998; Mir et al., 1998a, 1999), liver (Heller et al., 1996; Suzuki et al., 1998), skin (Titomirov et al., 1991; Zhang et al., 1996), tumors (Heller et al., 2000; Wells et al., 2000; Heller and Coppola, 2002), mouse testis (Muramatsu et al., 1997, 1998), and so on (Andréand Mir, 2004).

The mechanisms by which electric pulses mediate DNA transfer into target cells are not well understood. Nevertheless, there is common agreement that for improved DNA transfer into tissue, cells in that tissue must be permeabilized. Such per-meabilization can be achieved using simple runs of short square-wave electric pulses (in the range of 100 ?sec) (Mir et al., 1991b; Gehl et al., 1999; Miklavcˇicˇet al., 2000). This kind of pulse has been widely used for the local delivery of non-permeant anticancer drugs (such as bleomycin or cisplatin) in a form of treatment termed “antitumor electrochemotherapy”(Mir et al., 1991a, 1998b; Glass et al., 1997; Sersa et al., 1998; Rodriguez et al., 2002). Indeed, the delivery to tumors of, for example, eight pulses of 1300 V/cm and 100 ?sec either in vitro or in vivo is sufficient to induce transient rearrangements of the cell membrane that allow nonpermeant anticancer molecules such as bleomycin to enter the cell by diffusion and to fully ex-ert their cytotoxic activity (Mir et al., 1991b; Poddevin et al., 1991; Gehl et al., 1998).

These short permeabilizing electric pulses have also been shown to increase the transfer of plasmid DNA into several tis-sue types (Heller et al., 1996, 2000). However, another type of square-wave electric pulse was applied to muscles (Aihara and Miyazaki, 1998; Mir et al., 1999), tumors (Rols et al., 1998), liver (Suzuki et al., 1998), and some other tissues (André and Mir, 2004), and was found to be more effective for DNA elec-trotransfer (Mir et al., 1999; Heller et al., 2000). These pulses usually are of lower voltage but much longer duration (in the

1Vectorology and Gene Transfer, UMR 8121 CNRS, Institute Gustave Roussy, F-94805 Villejuif, France. 2Department of Biology, Vytautas Magnus University, LT-44404 Kaunas, Lithuania.

3U 266 INSERM-FRE 2463 CNRS, Faculté de Pharmacie, Université Paris 5, F-75270 Paris, France.

4Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia.

1194

IN VIVO DNA ELECTROTRANSFER1195

range of tens of milliseconds) (Aihara and Miyazaki, 1998; Rols et al., 1998; Mir et al., 1999; Bettan et al., 2000; Matsumoto et al., 2001). It is assumed that this type of pulse mediates DNA transfer into cells by inducing two distinct effects that include cell permeabilization (like the short pulses) and DNA elec-trophoretic migration during the delivery of the electric field (Klenchin et al., 1991; Sukharev et al., 1992; Neumann et al., 1996; Mir et al., 1999; Golzio et al., 2002). The double role of the electric pulses in in vivo DNA electrotransfer was demon-strated by using combinations of electric pulses consisting of high-voltage, short pulses (or HVs; e.g., 800 V/cm and 100?sec) followed by low-voltage, long pulses (or LVs; e.g., 80 V/cm and 100 msec) (Bureau et al., 2000; S?atkauskas et al., 2002). I n a previous study we found that these HV and LV pulses can be separated by various lag times between the HV and LV pulses without significant loss in transfection effi-ciency. These lag times ranged up to 300 sec for a combina-tion of one HV and one LV, and up to 3000 sec for a combi-nation of one HV and four LV (S?atkauskas et al., 2002).

Taking into account these lag times between the HV and LV pulses, we thought it possible to characterize separately the re-spective importance of the two effects of the electric fields—electropermeabilization and electrophoresis—on DNA electro-transfer efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid DNA

We used plasmid pXL3031 (pCMV-Luc?) containing the cytomegalovirus promoter (nucleotides 229–890 of pcDNA3;

I nvitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) inserted upstream of the sequence for luc, encoding a modified cytosolic wild-type firefly lucif-erase (Soubrier et al., 1999). We prepared plasmid DNA ac-cording to the usual procedures (Ausubel et al., 1994). Alter-natively, we also used plasmid pEGFP-N1 (BD Biosciences Clontech, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France), featuring the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the CMV promoter and prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; GI BCO/I nvitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France) with an EndoFree Plasmid Giga kit (Qiagen, Courtabeuf, France). Animals

For all experimental procedures we anesthetized female, 7-to 9-week-old C57BL/6 mice by intraperitoneal administration of the anesthetics ketamine (Ketalar, 100 mg/kg; Panpharma, Fougères, France) and xylazine (Rompun, 40 mg/kg; Bayer, Puteaux, France). Before performing the experiments subject legs were shaved with an electric shaver. At least 10 muscles (5 mice) were included in each experimental group for lucifer-ase determinations. In the case of the GFP qualitative data, four muscles were used for each experimental condition.

DNA injection

For the luciferase experiments, we injected 3 ?g of plasmid DNA prepared in 30 ?l of 0.9% NaCl. In most of our experiments (see Figs. 1–3) we supplemented the DNA solution with heparin (120 IU/ml; Laboratoires Leo, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France;1 mg of the heparin [MW 10,000–12,000] corresponded to ap-proximately 137 IU). We injected the DNA into tibialis cranialis muscles, using a Hamilton syringe with a 26-gauge needle. Be-cause the quality of injection of the plasmid may affect transfec-tion efficacy, all injections within a given experiment were per-formed by the same well-trained investigator. For GFP experiments, 4 ?g in 20 ?l of PBS was injected into each treated tibialis cranialis muscle, always in the absence of heparin. DNA electrotransfer

HV and LV pulse combinations were generated by a device consisting of square-wave electropulsator (PS-15; Jouan, St. Herblain, France) and a microprocessor-driven switch/function generator built at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering at the University of Ljubljana (Ljubljana, Slovenia). The device al-lowed for precise control of every electrical parameter of HV and LV pulse combinations (S?atkauskas et al., 2002).

HV and LV pulse combinations were delivered soon (40?15 sec) after intramuscular DNA injection. I n all the experi-ments we fixed the lag between HV and LV to 1 sec. For pulse delivery to the muscles we used stainless plate electrodes 4.4 mm apart. The 1-cm plates encompassed the whole leg of each mouse. To ensure good contact between the tibialis cranialis muscle of the exposed leg and the plates of the electrodes a conductive gel was used. Electric field values (in volts per cen-timeter) are always expressed in terms of the ratio of the volt-age applied (volts) to the distance between the electrodes (cen-timeters).

For the GFP experiments the pulse combinations were de-livered with a Cliniporator (IGEA, Carpi, Modena, Italy) gen-erator and electrodes (5 mm apart) from the same company. Luciferase activity measurement

We killed the mice 2 days after DNA electrotransfer. We re-moved and homogenized the muscles (net weight, approxi-mately 60 mg) in 1 ml of cell culture lysis reagent solution (10 ml of cell culture lysis reagent; Promega, Charbonnières, France), diluted with 40 ml of distilled water and supplemented with one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, we assessed the luciferase activity in 10 ?l of the super-natant, using a Wallac Victor2luminometer (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA), by integration of the light produced over 1 sec, starting after the addition of 50 ?l of luciferase assay substrate (Promega) to the muscle lysate. We collected the results from the luminometer in relative light units (RLU). Calibration with purified firefly luciferase protein showed that 106RLU corresponds to approximately 70 ng of expressed luciferase. We expressed the final results as picograms of luciferase per muscle.

GFP fluorescence observations

We killed the mice 3 days after the injection of pEGFP-N1 plasmid and observed the transfected tissue with an MZ12 flu-orescence stereomicroscope with a GFP Plus filter set (excita-tion filter, 480/40 nm; dichroic mirror, 505 nm LP; barrier fil-ter, 510 nm LP) (Leica, Rueil-Malmaison, France). After removal of the leg skin, pictures were taken with a digital cooled

color camera (AxioCam HRc; Zeiss, Le Pecq, France), and quantification of GFP expression was made by software (Ax-

ioVision Light Edition, release 4.1.1.0; Zeiss) integration of the light detected by the camera. Pictures were taken either at a constant exposure time (100 msec) or at a variable exposure time, that is, allowing the camera to adjust the exposure time to acquire an equivalent amount of light from picture to pic-ture. Each experimental condition was repeated four times (four muscles treated). Quantitative analysis was done by determin-ing the mean density of the green color in these images, using a relative scale with 256 levels of intensity.

Statistical analysis

For statistical comparison of several groups we used the two-tailed Student t test for unpaired values. In the figures we re-ported luciferase expression data as means?SD.

RESULTS

In the luciferase experiments, because of the high sensitivity of the measurements, we injected a solution of plasmid DNA sup-plemented with low amounts of heparin (120 IU/ml). Heparin at this dose causes a large decrease in the spontaneous uptake of DNA by the muscle but does not significantly impair the efficacy of DNA electrotransfer into the muscle fibers (S?atkauskas et al., 2001). Therefore, the respective contributions of HV and LV

pulses to the efficiency of DNA electrotransfer can be analyzed more precisely in the presence of heparin. In addition, we fixed the lag time between HV and LV pulse(s) to 1 sec. Influence of HV pulse duration and number

To analyze the role of the electropermeabilizing (HV) pulses we used LV pulses giving the best level of gene expression ac-cording to previous data (S?atkauskas et al., 2002). Therefore we fixed the LV component parameters to four LVs of 80 V/cm and 100-msec duration, with a delay between pulses of 1 sec.

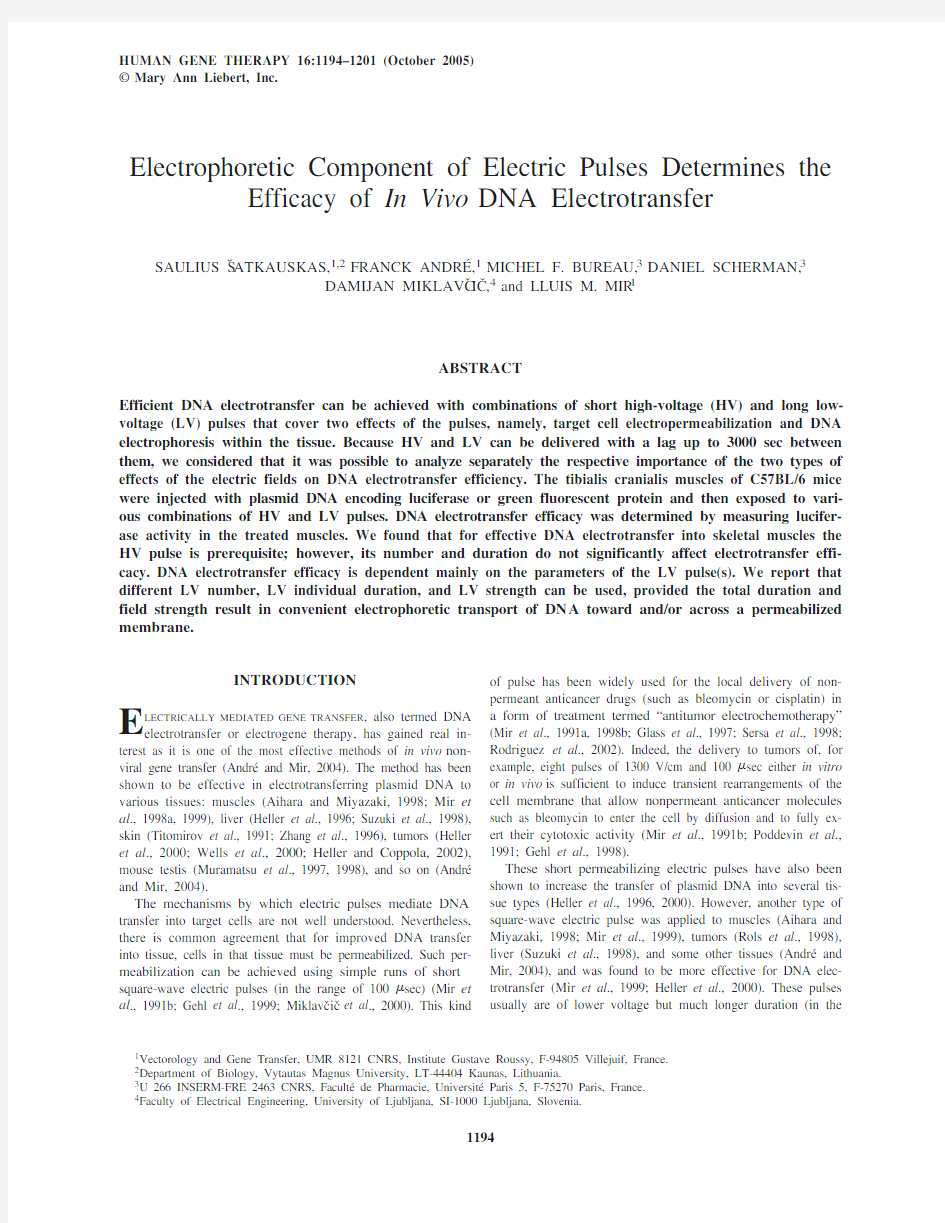

We tried to improve muscle permeabilization by increasing either the number (from one to eight) or the duration (from 100 to 500 ?sec) of the HV pulses. As shown in Fig. 1, neither an increase in HV duration, nor an increase in HV pulse number, significantly enhanced muscle transfection.

Influence of LV pulse number

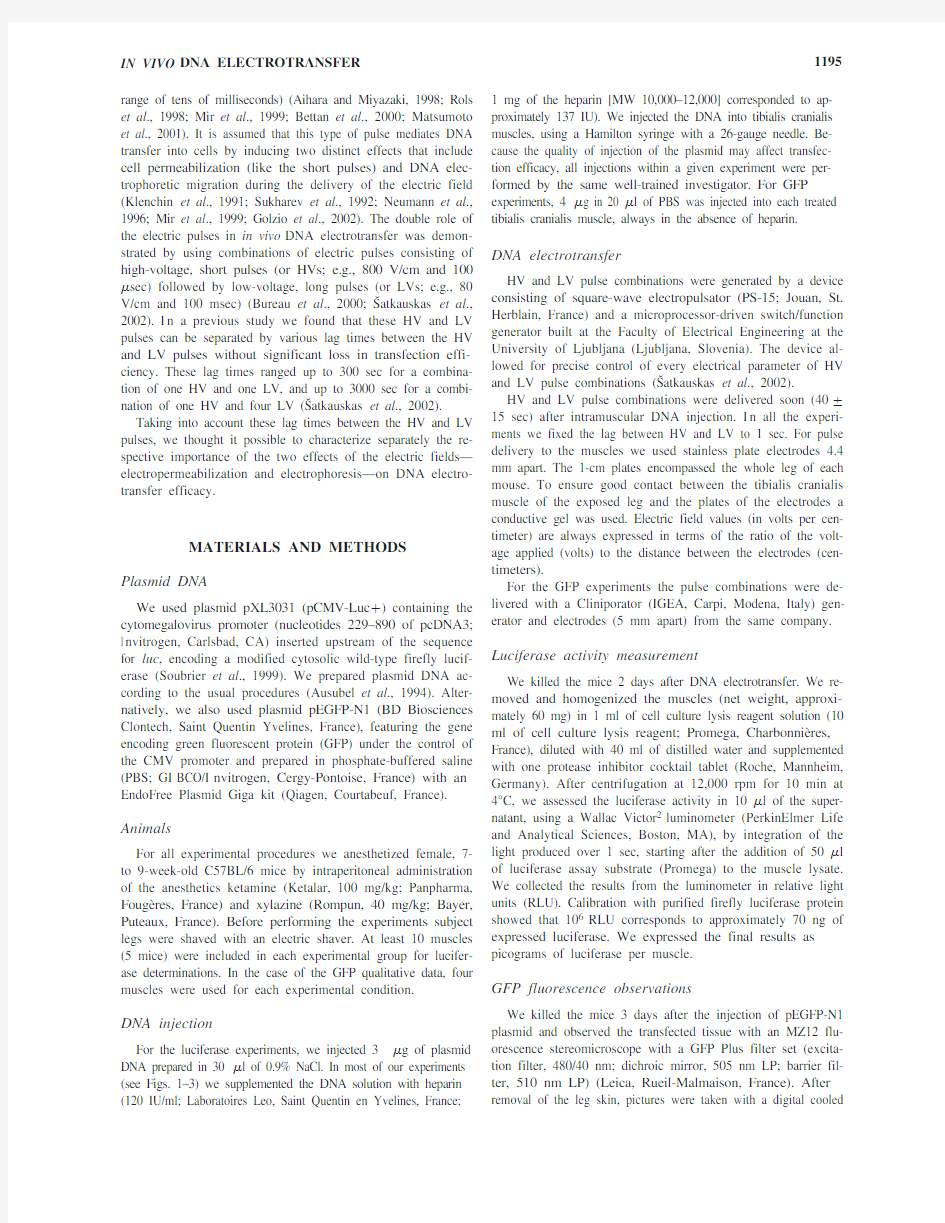

As a consequence of the results shown in Fig. 1, we always used a single HV pulse of 800 V/cm and 100 ?sec to analyze the role of the LV component. First, we examined the influence of the number of LVs. We fixed LV pulse strength at 80 V/cm, with a duration of 100 msec, and the delay between LVs at 1 sec. Luciferase expression markedly increased when we in-creased LV number from one to four (Fig. 2A). Consistent with previous data (S?atkauskas et al., 2002), with four LVs the lu-ciferase expression was 10 times higher than with one LV. No further significant increase was observed with a larger number (six or eight) of LV pulses (Fig. 2A).

Subsequent experiments on the influence of pulse number on gene transfer efficacy were performed with 50-msec LV(s) (Fig. 2B). We observed the same trend as in the case of 100-msec LV(s) (Fig. 2A). In both cases the beginning of the plateau in luciferase gene expression started at a total pulse duration of 400 msec. Again, no further significant increase was observed with increased number (12 or 16) of LV pulses. These data also sug-gested that similar levels of DNA electrotransfer and gene ex-pression may be achieved with different combinations of LV pulse number and duration. To test this hypothesis, we used four different combinations of number (n) and duration (d) of LVs, such that the product n?d was constant and equal to 400 msec (Fig. 2C). A tendency to a progressive decrease in luciferase gene expression with the concomitant decrease in individual pulse duration and increase in pulse number was found (Fig. 2C). For instance, HV and LV combinations using one LV of 400 msec resulted in about two times higher luciferase gene ex-pression compared with eight LVs of 50 msec (p?0.001). Influence of LV pulse strength

Figure 3 shows the dependence of DNA electrotransfer and expression on the electric field strength of the LV pulses. We examined LV pulse strengths ranging from 20 to 100 V/cm. At low electric field strengths (20 and 40 V/cm), luciferase ex-pression was not significantly increased (p?0.05) in compar-ison with that achieved with the HV pulse alone. At 60 V/cm LV pulses started to play a significant role and luciferase ex-pression was already more than 100 times higher than that ob-tained by HV pulse alone. We obtained the highest values of luciferase expression with LVs of 100 V/cm (Fig. 3). Combination of LV pulse strength and duration In this set of experiments, we aimed to analyze whether the decrease in efficacy when using LVs of lower field strength

S?ATKAUSKAS ET AL.

1196

FIG. 1.Luciferase expression after DNA electrotransfer

based on combinations of one or eight HV pulses (800 V/cm;

0.1, 0.2, or 0.5 msec) and four LV pulses (80 V/cm and 100

msec) (n HV?4LV pulse combination). Data are presented as

means?SD. The significance of differences between each of

the n HV?4LV groups was calculated by t tests; NS, not sig-

nificant. Each column represents results from at least 18 mus-

cles treated in two experiments.

IN VIVO DNA ELECTROTRANSFER

1197

(e.g., 60 V/cm, as in Fig. 3) could be counterbalanced by the use of longer pulses. We thus compared several combinations of one HV and four LVs, using LVs of either 60 or 80 V/cm and individual pulse durations between 100 and 800 msec (Fig. 4).

With one HV and four LVs at a pulse strength of 80 V/cm we obtained similar luciferase expression at the three LV pulse durations tested (100, 200, and 400 msec) (Fig. 4). With one HV and four LVs at a pulse strength of 60 V/cm and a pulse duration of 400 msec we obtained a result similar to those achieved under the previously tested conditions at 80 V/cm,whereas at a longer pulse duration (800 msec), luciferase ex-pression was significantly higher with respect to the 80-V/cm,100-msec pulses (Fig. 4).

GFP fluorescence observations

The distribution and intensity of the fluorescence within mus-cles after electrotransfer of the GFP gene were qualitatively and semiquantitatively measured with a fluorescence stereo microscope (Fig. 5). For the electrotransfer of the GFP gene we used one HV of 100 ?sec and 800 V/cm followed after a 1-sec delay by one 400-msec LV pulse of either 60, 80, or 100 V/cm. Pictures were taken either at a constant exposure time (100 msec; Fig. 5A–C) or

at a variable exposure time, that is, allowing the camera to adjust the exposure time to acquire an equivalent amount of light from picture to picture (Fig. 5D–F). These pictures represent the images observed in four muscles for each experimental condition. Two se-ries of pictures are reported to show the reproducibility of the re-sults as well as the large increase in fluorescence with the increase in field strength of the LV pulses (Fig. 5A–C). Quantitative anal-ysis of the mean density of the green color in these images sus-tains the qualitative data: at a relative scale with 256 levels of in-tensity, levels 41 (left muscle) and 33 (right muscle) were reached at 60 V/cm (Fig. 5A), whereas levels 111 and 89 were reached at 80 V/cm (Fig. 5B) and levels 138 and 127 were reached at 100V/cm (Fig. 5C). These pictures also show that the volume of trans-fected (fluorescent) muscle is similar whatever the LV field strength (Fig. 5D–F). These data suggest that the overall increase in fluorescence results from an increase in the fluorescence of each fiber, and not from an increase in the volume (and thus the num-ber) of muscle fibers susceptible to fluorescence.

DISCUSSION

Using combinations of HV and LV pulses, we previously showed that in vivo

DNA electrotransfer is a multistep process

FIG. 2.Luciferase expression after DNA electrotransfer based on a combination of one HV pulse (800 V/cm and 100ìsec) and a various number of LV pulses (80 V/cm and 100msec) (HV ?n LV pulse combinations): (A ) using various num-bers (n ) of LV pulses, each with a duration d of 100 msec; (B )using various numbers (n ) of LV pulses, each with a duration d of 50 msec; (C ) using various numbers (n ) of LV pulses of various durations d such that the product n ?d is constant and equal to 400 msec. Data are presented as means ?SD. The sig-nificance of differences between neighboring groups was cal-culated by t tests and is indicated by asterisks (*p ?0.05; **p ?0.01; ***p ?0.001; NS, not significant). Each column repre-sents results from 10 muscles treated during one experiment (A and B ) or from at least 16 muscles treated in two experiments (C ).

that includes DNA distribution, cell permeabilization, and DNA

electrophoresis (S

?atkauskas et al ., 2002). We found that the role of the HV pulse was limited mainly to cell permeabilization,whereas LV pulses had a direct effect on DNA, probably DNA electrophoresis. However, the interplay between HV and LV pulses, and how the parameters of HV and LV pulses influ-enced DNA electrotransfer, were still unclear. In elegant in vitro experiments using 1, 2, and 3% agarose gels and pulses simi-lar to our LV pulses, Zaharoff and Yuan (2004) analyzed DNA electromobility: they showed that, using pulses of 10 to 99 msec at 100 to 400 V/cm (comparable to our LV pulses), plasmids were transported over distances longer, by two to three orders of magnitude, than those achieved with pulses of 99 ?sec at 2.0 kV/cm (comparable to our HV pulses). We discuss here both old and new data on the influence of HV and LV pulses on DNA electrotransfer efficacy in light of these in vitro data.It was known that one 100-?sec HV pulse alone is not suf-ficient for efficient DNA electrotransfer (S

?atkauskas et al .,2002); this could be due to insufficient electrophoretic trans-port of DNA into the tissue. Interestingly, the data reported here show that neither HV pulse duration nor the number of HV pulses had an effect on DNA electrotransfer efficiency. Because eight HVs permeabilize muscle to a significantly greater extent than one HV (Bureau et al ., 2000), it seems possible that the achievement of optimal permeabilization by the HV is not crit-ical for effective DNA electrotransfer, at least under the ex-perimental conditions in which LV pulses are optimal or close to optimal (e.g., four LVs at 80 V/cm and 100 msec). Thus mus-cle must be permeabilized to some extent but not necessarily to the optimal level. This is also supported by our previous stud-ies on the kinetics of membrane resealing after the permeabi-lization of muscle with one HV of 800 V/cm and 100 ?sec:even though the level of muscle permeabilization after one HV pulse significantly decreased after 300 sec, high and similar lev-

els of DNA electrotransfer and gene expression were still

reached with combinations of HV and LVs in which the four

LVs were delivered even 3000 sec after the HV (S

?atkauskas

et al ., 2002). Nevertheless, HV delivery is prerequisite, because the reverse order of the pulses, that is, an LV plus HV sequence,resulted in levels of DNA expression as low as those obtained

by the delivery of one HV pulse alone (S

?atkauskas et al ., 2002).Contrary to the HV pulse, DNA electrotransfer efficacy is highly dependent on the electrical parameters of the LV pulses.For individual LV durations of 100 or 50 msec (Fig. 2A and B),DNA electrotransfer efficacy increased with the number and/or individual duration of the LV pulses until a plateau was reached,when the total duration of the LVs reached 400 msec. It is inter-esting to note that, with respect to total LV pulse duration, pat-terns of luciferase expression for both individual LV durations were similar (Fig. 2A and B). Because electrophoretic transport (and thus migration distance) in a given medium and at a given voltage depends mainly on the duration of the applied electric field, the results in Fig. 2A and B argue in favor of a true elec-trophoretic role for the LV pulses. The importance of the elec-trophoretic effects on DNA electrotransfer efficacy can be ex-plained by the fact that DNA must overcome physical barriers in the interstitial space before achieving close contact with the per-meabilized plasma membrane and crossing it. Electrophoretic transport should thus ensure DNA interaction with the permeabi-lized cell membrane, which explains why the efficiency of DNA electrophoresis governs the efficacy of DNA electrotransfer.When comparing transfection efficacy levels produced by an identical total duration of LV pulses, but using four different du-rations for the individual LV pulses, significantly higher levels of gene expression were achieved with the longest individual LV pulses (Fig. 2C). At first glance, this does not seem compatible with the electrophoretic effect of LV pulses suggested previously.However, “compatibility” with a pure electrophoretic effect can

S

?ATKAUSKAS ET AL.1198

FIG. 3.Luciferase expression after DNA electrotransfer based on a combination of one HV pulse (800 V/cm and 100?sec) and four 100-msec LV pulses as a function of the strength of the LV pulses. Data are presented as means ?SD. The sig-nificance of differences between neighboring groups was cal-culated by t tests and is indicated by asterisks (*p ?0.05;***p ?0.001; NS, not significant). Each column represents re-sults from 10 muscles treated in one experiment.

FIG. 4.Luciferase expression after DNA electrotransfer by combinations of one HV pulse (800 V/cm, 100 ?sec) and four LV pulses as a function of LV pulse strength and duration. Data are presented as means ?SD. A statistically significant differ-ence, calculated by t tests, was found only between the 60-V/cm, 800-msec group and the 80-V/cm, 100-msec group, and is indicated by an asterisk (*p ?0.05). Each column represents results from 10 muscles treated in one experiment.

IN VIVO DNA ELECTROTRANSFER

1199

be shown by taking into account the in vitro results of Zaharoff and Yuan (2004) on the mobility in agarose gels of DNA mole-cules exposed to pulse durations similar to those of the LV pulses described here. The agarose gels used by these authors are sup-posed to mimic interstitial barriers in biological tissues. They found that the dependence of plasmid electromobility on pulse duration was not linear and displayed a sigmoid shape: at shorter durations electromobility is low, whereas with longer durations it increases, reaching a plateau at 50 msec in 1% agarose gels,and at higher pulse duration (80–100 msec) in more concentrated gels (2–3% agarose). Indeed, for a plasmid to move through the narrow passages in agarose gels, random coiled DNA should elongate in the direction of motion and shrunk in the perpendic-ular direction (Zaharoff and Yuan, 2004). Then, if a long LV pulse is substituted by multiple shorter LV pulses, separated by 1 sec, the elongated plasmid relaxes between the pulses. The con-secutive LV pulses must again align the plasmid along the di-rection of the electric field. This alignment takes time and there-fore electrophoresis of the plasmid is not as efficient as in the case of a single but long pulse. Moreover, because tissue struc-ture is much more complex than an agarose gel, electromobility of the plasmid should still be more dependent on pulse duration.Plasmid DNA electrophoresis in tissues is further supported by another study by Zaharoff et al . (2002) showing that in tumors,electric pulses similar to the LV pulses used here can actually pro-duce the electrophoretic migration of DNA over distances of about 1 ?m. Thus the LV pulses should be sufficient to bring the DNA from the bulk of the injected liquid into close contact with the permeabilized plasma membrane of the muscle cell and/or to con-tribute to translocation of the DNA through the permeabilized membrane. In addition to pure electrophoretic effects, it cannot be excluded that LV pulses might increase the myofiber perme-abilization created by the HV pulse (in particular for the longest and more intense LV pulses). This might contribute to enhanced electrotransfer efficacy. However, the results of Fig. 1 clearly show that the level of cell permeabilization is not of primary im-portance. Moreover, the results of Fig. 2 strongly argue in favor of the hypothesis that efficacy of gene electrotransfer is governed mainly by the electrophoretic forces of the LV pulses.

When we tested various LV pulse field strengths (Fig. 3),the same low level of luciferase expression was achieved with LV pulses up to 40 V/cm than with the HV pulse alone (equiv-alent to the delivery of an LV at 0 V/cm). Low transfection ef-ficiency using LV pulses of 20 or 40 V/cm may be explained by the absence of an “electrophoretic field” in the muscle,caused by the voltage drop across the skin. Indeed, even if skin is electropermeabilized, it still remains highly nonconductive,provoking a substantial voltage drop (data not shown). Thus,on the one hand, it is possible that with LVs of 20 or 40 V/cm the electrophoretic force in the muscle tissue was negligible and, on the other hand, that an increase in LV pulse amplitude from 60 to 100 V/cm resulted in a progressive increase in lu-ciferase expression (Fig. 3), according to the basic rules of elec-trophoresis. Pulses of 60 V/cm and 20 to 83 msec in duration do not contribute to muscle fiber permeabilization (Gehl and Mir, 1999; Bureau et al ., 2000), even if they are delivered af-ter one 100-?sec HV (Mir et al ., in preparation). Thus, using pulses of 60 V/cm, only the electrophoretic effects of such pulses should be observed. I nterestingly, the data reported in Fig. 4 demonstrate that long-enough pulses (400 msec) at 60V/cm result in luciferase expression similar to that achieved with the 80-V/cm pulses, and that much longer pulses (800msec) result in still higher luciferase expression. So, the de-

creased electrotransfer efficacy with the 60-V/cm LVs (at a du-

FIG. 5.GFP expression in tibialis cranialis muscles after DNA electrotransfer by combinations of one HV pulse (800 V/cm, 100?sec) and one LV pulse of 400 msec and either 60, 80, or 100 V/cm. (A and D ) LV of 60 V/cm; (B and E ) LV of 80 V/cm; (C and F ) LV of 100 V/cm. (A –C ) Camera exposure time was fixed at 100 msec. (D ) Exposure times were 243 msec (left muscle) and 392msec (right muscle). (E ) Exposure times were 36 msec (left muscle) and 55 msec (right muscle). (F ) Exposure time was 23 msec for both muscles. Representative images of four muscles treated under each of the experimental conditions are shown.

ration of 100 msec) can be fully compensated by an increase in pulse duration, which is in clear agreement with elec-trophoresis principles.

As expected from the results with the luciferase gene, the in-crease in field strength of the LVs resulted in an increase in GFP fluorescence (Fig. 5). Qualitative and quantitative data clearly showed that this increase in fluorescence resulted from the greater fluorescence of each fiber; the volume of tissue af-fected by the electrotransfer remained the same. This is in agree-ment with the previous assignment of roles of the HV and LV pulses. The experiments reported in Fig. 5D–F show that the same volume of tissue was affected by the DNA electrotrans-fer, which was expected because the same HV pulse was used under the three experimental conditions. Within the volume of tissue affected by the HV pulse, the fluorescence of the indi-vidual fibers increased with an increase in the strength of the LVs from 60 to 100 V/cm (Fig. 5A–C). The increase in elec-trophoretic effect should bring more plasmid molecules in con-tact with the electropermeabilized membrane and, conse-quently, more plasmid molecules should be able to cross the plasma membrane, resulting in the observed enhancement of the efficacy of DNA electrotransfer.

The electrophoretic effect of LV pulses may contribute to in-creased transfection efficacy in several ways. First, they may induce sufficient DNA electrophoresis to bring plasmid DNA from the bulk of the interstitium into contact with permeabi-lized membranes. Second, when the plasmid molecules are al-ready in contact with permeabilized membranes, the elec-trophoretic force of LV pulses may facilitate translocation of the plasmid molecules into the cells.

In conclusion, consistent with previous in vitro reports and our previous in vivo work, the present study confirms that ef-ficient electrogene transfer is based on at least two distinct ef-fects exerted by the electric pulses: cell permeabilization and DNA electrophoresis. The results of the current study high-light the importance of in vivo DNA electrophoresis in elec-trotransfer efficacy. We demonstrate that, provided some mus-cle permeabilization is achieved by the prerequisite HV pulse, DNA electrotransfer efficiency is governed by the elec-trophoretic effect of the LV pulse(s). These results provide new avenues for further optimization of in vivo electrogene therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research has been supported through various grants from the CNRS; the I nstitut Gustave-Roussy; Aventis-Gencell; the EU Commission (Project QLK3-1999-00484 within the fifth FP); the Ministry of Education, Science, and Sports (MESS) of the Republic of Slovenia; and the Lithuanian State Science and Studies Foundation (K-C 17/2). Exchanges have been possible also thanks to the bilateral program of scientific, technological, and cultural cooperation between the CNRS (Project 5386) and MESS (Proteus program). The authors acknowledge Tamsin Wright Carpenter for linguistic revisions of this paper and also thank the staff of the Service Commun d’Expérimentation An-imale of the IGR for animal maintenance. During part of this work, S.S?. was the recipient of a research grant from Aventis to L.M.M.

REFERENCES

AIHARA, H., and MIYAZAKI, J. (1998). Gene transfer into muscle by electroporation in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 16,867–870.

ANDRé, F., and MI R, L.M. (2004). DNA electrotransfer: I ts princi-ples and an updated review of its therapeutic applications. Gene Ther. 11(Suppl. 1),S33–S42.

AUSUBEL, F.M., BRENT, R., K NGSTON, R.E., MOORE, D., SEI DMAN, J.G., SMI TH, J.A., and STRUHL, K. (1994). Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. (John Wiley & Sons, New York). BETTAN, M., EMMANUEL, F., DARTEI L, R., CAI LLAUD, J.M., SOUBRIER, F., DELAERE, P., BRANELEC, D., MAHFOUDI, A., DUVERGER, N., and SCHERMAN, D. (2000). High-level protein secretion into blood circulation after electric pulse-mediated gene transfer into skeletal muscle. Mol. Ther. 2,204–210.

BUREAU, M.F., GEHL, J., DELEUZE, V., MIR, L.M., and SCHER-MAN, D. (2000). Importance of association between permeabiliza-tion and electrophoretic forces for intramuscular DNA electrotrans-fer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1474,353–359.

GEHL, J., and MIR, L.M. (1999). Determination of optimal parameters for in vivo gene transfer by electroporation, using a rapid in vivo test for cell permeabilization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261,377–380. GEHL, J., SKOVSGAARD, T., and MIR, L.M. (1998). Enhancement of cytotoxicity by electropermeabilization: An improved method for screening drugs. Anticancer Drugs 9,319–325.

GEHL, J., S?RENSEN, T.H., N ELSEN, K., RASKMARK, P., NIELSEN, S.L., SKOVSGAARD, T., and MIR, L.M. (1999). In vivo electroporation of skeletal muscle: Threshold, efficacy and relation to electric field distribution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1428,233–240. GLASS, L.F., JAROSZESKI, M., GI LBERT, R., REI NTGEN, D.S., and HELLER, R. (1997). I ntralesional bleomycin-mediated elec-trochemotherapy in 20 patients with basal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 37,596–599.

GOLZIO, M., TEISSIE, J., and ROLS, M.P. (2002). Direct visualiza-tion at the single-cell level of electrically mediated gene delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99,1292–1297.

HELLER, L., JAROSZESKI, M.J., COPPOLA, D., POTTINGER, C., GILBERT, R., and HELLER, R. (2000). Electrically mediated plas-mid DNA delivery to hepatocellular carcinomas in vivo. Gene Ther. 7,826–829.

HELLER, L.C., and COPPOLA, D. (2002). Electrically mediated de-livery of vector plasmid DNA elicits an antitumor effect. Gene Ther. 9,1321–1325.

HELLER, R., JAROSZESKI, M., ATKI N, A., MORADPOUR, D., GILBERT, R., WANDS, J., and NICOLAU, C. (1996). In vivo gene electroinjection and expression in rat liver. FEBS Lett. 389,225–228. KLENCH

I

N, V.A., SUKHAREV, S.

I

., SEROV, S.M., CHER-NOMORDIK, L.V., and CHIZMADZHEV, Y. (1991). Electrically induced DNA uptake by cells is a fast process involving DNA elec-trophoresis. Biophys. J. 60,804–811.

MATSUMOTO, T., KOMORI, K., SHOJI, T., KUMA, S., KUME, M., YAMAOKA, T., MORI, E., FURUYAMA, T., YONEMITSU, Y., and SUGIMACHI, K. (2001). Successful and optimized in vivo gene transfer to rabbit carotid artery mediated by electronic pulse. Gene Ther. 8,1174–1179.

MIKLAVCˇICˇ, D., S?EMROV, D., MEKID, H., and MIR, L.M. (2000).

A validated model of in vivo electric field distribution in tissues for electrochemotherapy and for DNA electrotransfer for gene therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1523,73–83.

MI R, L.M., BELEHRADEK, M., DOMENGE, C., ORLOWSKI, S., PODDEVIN, B., BELEHRADEK, J., SCHWAAB, G., LUBOINSKI, B., and PAOLETTI, C. (1991a). [Electrochemotherapy, a new anti-tumor treatment: first clinical trial]. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 313,613–618. MIR, L.M., ORLOWSKI, S., BELEHRADEK, J., and PAOLETTI, C. (1991b). Electrochemotherapy potentiation of antitumour effect of bleomycin by local electric pulses. Eur. J. Cancer 27,68–72.

S?ATKAUSKAS ET AL.

1200

IN VIVO DNA ELECTROTRANSFER1201

MIR, L.M., BUREAU, M.F., RANGARA, R., SCHWARTZ, B., and SCHERMAN, D. (1998a). Long-term, high level in vivo gene ex-pression after electric pulse-mediated gene transfer into skeletal mus-cle. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 321,893–899.

MIR, L.M., GLASS, L.F., SERSA, G., TEISSIE, J., DOMENGE, C., MIKLAVCˇICˇ, D., JAROSZESKI, M.J., ORLOWSKI, S., REI NT-GEN, D.S., RUDOLF, Z., BELEHRADEK, M., GI LBERT, R., ROLS, M.P., BELEHRADEK, J., BACHAUD, J.M., DECONTI, R., STABUC, B., CEMAZAR, M., CONI NX, P., and HELLER, R. (1998b). Effective treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous malig-nant tumours by electrochemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 77,2336–2342. MIR, L.M., BUREAU, M.F., GEHL, J., RANGARA, R., ROUY, D., CAILLAUD, J.M., DELAERE, P., BRANELLEC, D., SCHWARTZ, B., and SCHERMAN, D. (1999). High-efficiency gene transfer into skeletal muscle mediated by electric pulses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96,4262–4267.

MURAMATSU, T., SHI BATA, O., RYOKI, S., OHMORI, Y., and OKUMURA, J. (1997). Foreign gene expression in the mouse testis by localized in vivo gene transfer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com-mun. 233,45–49.

MURAMATSU, T., NAKAMURA, A., and PARK, H.M. (1998). In vivo electroporation: A powerful and convenient means of nonviral gene transfer to tissues of living animals [review]. Int. J. Mol. Med. 1,55–62. NEUMANN, E., KAKORIN, S., TSONEVA, I., NIKOLOVA, B., and TOMOV, T. (1996). Calcium-mediated DNA adsorption to yeast cells and kinetics of cell transformation by electroporation. Biophys. J. 71,868–877.

PODDEVIN, B., ORLOWSKI, S., BELEHRADEK, J., and MIR, L.M. (1991). Very high cytotoxicity of bleomycin introduced into the cy-tosol of cells in culture. Biochem. Pharmacol. 42(Suppl.),S67–S75. RODRIGUEZ, C., BARROSO, B., ALMANZA, E., CRISTOBAL, M., and GONZALEZ, R. (2002). Electrochemotherapy in primary and metastatic skin tumors: Phase II trial using intralesional bleomycin. Arch. Med. Res. 32,273–276.

ROLS, M.P., DELTEIL, C., GOLZIO, M., DUMOND, P., CROS, S., and TEI SSI E, J. (1998). In vivo electrically mediated protein and gene transfer in murine melanoma. Nat. Biotechnol. 16,168–171. S?ATKAUSKAS, S., BUREAU, M.F., MAHFOUDI, A., and MIR, L.M. (2001). Slow accumulation of plasmid in muscle cells: Supporting evidence for a mechanism of DNA uptake by receptor-mediated en-docytosis. Mol. Ther. 4,317–323.

S?ATKAUSKAS, S., BUREAU, M.F., PUC, M., MAHFOUDI, A., SCHERMAN, D., MIKLAVCˇICˇ, D., and MIR, L.M. (2002). Mech-anisms of in vivo DNA electrotransfer: respective contributions of cell electropermeabilization and DNA electrophoresis. Mol. Ther. 5, 133–140.SERSA, G., STABUC, B., CEMAZAR, M., JANCAR, B., MIKLAVCˇICˇ, D., and RUDOLF, Z. (1998). Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin: Potentiation of local cisplatin antitumour effective-ness by application of electric pulses in cancer patients. Eur. J. Can-cer 34,1213–1218.

SOUBRIER, F., CAMERON, B., MANSE, B., SOMARRIBA, S., DU-BERTRET, C., JASLI N, G., JUNG, G., CAER, C.L., DANG, D., MOUVAULT, J.M., SCHERMAN, D., MAYAUX, J.F., and CROUZET, J. (1999). pCOR: A new design of plasmid vectors for nonviral gene therapy. Gene Ther. 6,1482–1488. SUKHAREV, S.

I

., KLENCH

I

N, V.A., SEROV, S.M., CHER-NOMORDIK, L.V., and CHIZMADZHEV, Y. (1992). Electropora-tion and electrophoretic DNA transfer into cells: The effect of DNA interaction with electropores. Biophys. J. 63,1320–1327. SUZUKI, T., SHI N, B.C., FUJI KURA, K., MATSUZAKI, T., and TAKATA, K. (1998). Direct gene transfer into rat liver cells by in vivo electroporation. FEBS Lett. 425,436–440.

TITOMIROV, A.V., SUKHAREV, S., and KISTANOVA, E. (1991). In vivo electroporation and stable transformation of skin cells of new-born mice by plasmid DNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1088,131–134. WELLS, J.M., LI, L.H., SEN, A., JAHREI S, G.P., and HUI, S.W. (2000). Electroporation-enhanced gene delivery in mammary tumors. Gene Ther. 7,541–547.

ZAHAROFF, D.A., and YUAN, F. (2004). Effects of pulse strength and pulse duration on in vitro DNA electromobility. Bioelectro-chemistry 62,37–45.

ZAHAROFF, D.A., BARR, R.C., LI, C.Y., and YUAN, F. (2002). Elec-tromobility of plasmid DNA in tumor tissues during electric field-mediated gene delivery. Gene Ther. 9,1286–1290.

ZHANG, L., LI, L., HOFFMANN, G.A., and HOFFMAN, R.M. (1996). Depth-targeted efficient gene delivery and expression in the skin by pulsed electric fields: an approach to gene therapy of skin aging and other diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 220,633–636.

Address reprint requests to:

Dr. Lluis M. Mir

UMR 8121 CNRS-Institut Gustave Roussy

39 Rue C. Desmoulins

F-94805 Villejuif Cédex, France

E-mail: luismir@igr.fr Received for publication February 20, 2005; accepted after re-vision July 28, 2005.

Published online: September 23, 2005.

浅谈标点符号的正确使用

一、故事引入 杜牧的《清明》一诗“清明时节雨纷纷,路上行人欲断魂。借问酒家何处有,牧童遥指杏花村。”大家都很熟悉,但如果把标点符号改动一下,就成了另一作品。有人巧妙短句将其改成了一首词:“清明时节雨,纷纷路上,行人欲断魂。借问酒家何处?有牧童遥指,杏花村。”还有人改成了一首优美隽永的散文:“清明时节,雨纷纷。路上,行人欲断魂。借问酒家:“何处有牧童?”遥指杏花村。 又如,常有人在一路边大小便,有人就在那立了块牌子:过路人等不得在此大小便。立牌人的本意是:“过路人等,不得在此大小便。”可没有点标点符号,于是被人认为是:“过路人,等不得,在此大小便。” 类似的故事不胜枚举,诸如一客栈“下雨天留客天留我不留”的对联,祝枝山写给一财主的对联“今年正好晦气全无财富进门”。可见,标点符号的作用举足轻重。语文课程标准对小学各阶段学生应该掌握的标点符号作了明确的规定和说明。因此,作为小学语文教师,不但要咬文嚼字,教会学生正确使用标点符号也不容忽视。下面,我就简单谈谈一些易错的标点符号的用法。 二、易错标点符号的用法例谈 (一)问号 1、非疑问句误用问号 如:他问你明天去不去公园。虽然“明天去不去公园”是一个疑问,但这个问句在整个句子中已经作了“问”的宾语,而整个句

子是陈述的语气,句尾应该用句号。又如:“我不晓得经理的心里到底在想什么。”句尾也应该用句号。 2、选择问句,中间的停顿误用问号 比如:宴会上我是穿旗袍,还是穿晚礼服?这是个选择问句,中间“旗袍”的后面应该用逗号,而不用问号。再有:他是为剥削人民的人去死的,还是为人民的利益而死的?这个句中的停顿也应该用逗号。 3、倒装句中误把问号前置 像这样一个句子:到底该怎么办啊,这件事?原来的语序是:这件事到底该怎么办啊? 倒装之后,主语放到了句末,像这种情况,一般问号还是要放在句末,表示全句的语气。 4、介于疑问和感叹语气之间的句子该如何使用标点符号 有的句子既有感叹语气,又有疑问的语气,这样的情况下,哪种语气强烈,就用哪个标点,如果确定两种语气的所占比重差不多,也可以同时使用问号和叹号。 (二)分号 1、句中未用逗号直接用分号 从标点符号的层次关系来看,应该是逗号之间的句子联系比较紧密,分号之间的句子则要差一个层次,这样看来,在一个句中,如果没有逗号径直用分号是错误的。比如:漓江的水真静啊,漓江的水真清啊,漓江的水真绿啊。这里句中的两处停顿就不能使用分号。再

编校一课丨连接号用法大全

编校一课丨连接号用法大全 《标点符号用法》新标准中,连接号删除长横线“——”,只保留三种形式:一字线“—”、半字线“-”、波纹线“~”。三种连接号的使用范围各不相同。一字线 一字线占一个字位置,比汉字“一”略长标示时间、地域等相 关项目间的起止或相关项之间递进式发展时使用一字线。例:1.沈括(1031—1095),宋朝人。 2.秦皇岛—沈阳将建成铁路客运专线。 3.人类的发展可以分为古猿—猿人—古人—新人这四个阶段半字线半字线也叫短横线,比汉字“一”略短,占半个字位置。用于产品型号、化合物名称、 代码及其他相关项目间的连接。例:1.铜-铁合金(化合物 名称) 2.见下图3-4(表格、插图编号) 3. 中关园3号院3-2-11室(门牌号) 4.010-********(电话号码) 5.1949-10-01(用阿拉伯数字表示年月日) 6.伏尔加河-顿河运河(复合名词)波纹线波纹线俗称波浪线,占一个字位置标示数值范围的起止时用波纹线,包括用阿拉伯数字表示的数值和由汉字数字构成的数值。例:1.10~30cm 2. 第七~九课常见问题1.在数值间使用连接号时,前后两个数值都需要加上计量单位吗?在标示数值范围时,用波纹线连接号。此时,在不引起歧义的情况下,只在后一数值后计量单位,用波纹线连接的两个

数值,其单位是一致的。例:500~1000公斤 2.“1996~现在”这样的用法对吗?不对。波纹线连接数字,“现在”不是数字,应改为“”到或“至”。“1996”后宜加“年”。 关注“木铎书声”,做优秀出版人木铎书声是北京师范大学出版科学研究院官方微信平台,致力于传播最新行业动态,促进出版职业人的发展。

连接号用法之深入辨析

连接号用法之深入辨析 王曜卿 第二轮修志,各地都是衔接上届志书的下限编修续志,续志书名也是千篇一律:在书名下加上断限。书名下断限的书写格式,规范写法为―(19xx-2000)‖,但采用这种写法的却不成主流。不规范的书写格式中,常见的是―(19xx~2000)‖,此外还有―(19xx-2000年)‖、―(19xx~2000年)‖、―(19xx年-2000年)‖、―(19xx年~2000年)‖,加上―-‖、―~‖两种符号自身宽度变化所产生的变体,不规范的写法就更多了。 志书断限中的连接号,没有引起人们的高度重视,由此所反映出来的,则是标点符号规范化和表达概念准确性的大问题。准确地说,是正确、规范地使用连接号,准确地表述时空范围之概念,准确地表述数值量之关系(或幅度)的大问题。 一、连接号的多种形式 连接号有多种形式,各自的作用、用途也不同。中华人民共和国国家标准(简称―国标‖)《标点符号用法》(GB/T 15834-1995)对连接号的规定: 4.13 连接号 4.13.1 连接号的形式为?-‘。连接号还有另外三种形式,即长横?——‘、半字线?-‘和浪纹?~‘。 4.13.2 两个相关的名词构成一个意义单位,中间用连接号。例如: a) 我国秦岭-淮河以北地区属于温带季风气候区,夏季高温多雨,冬季寒冷干燥。 b) 复方氯化钠注射液,也称任-洛二氏溶液(Ringer-Locke solution),用于医疗和哺乳动物生理学实验。 4.13.3 相关的时间、地点或数目之间用连接号,表示起止。例如: a) 鲁迅(1881-1936)中国现代伟大的文学家、思想家和革命家。 b) ?北京——广州‘直达快车 c) 梨园乡种植的巨峰葡萄今年已经进入了丰产期,亩产1000公斤~1500公斤。 4.13.4 相关的字母、阿拉伯数字等之间,用连接号,表示产品型号。例如: 在太平洋地区,除了已建成投入使用的HAW-4和TPC-3海底光缆之外,又有TPC -4海底光缆投入运营。 4.13.5 几个相关的项目表示递进式发展,中间用连接号。例如:

连接号用法

连接号用法 国家标准《标点符号用法》(GB/T15834—1995)把连接号分为一字线(—)、半字线(-)、浪纹线(~)和长横线(——)4种形式。 连接号的基本用法是把意义密切相关的词语、字母、数字连接成一个整体。连接号的基本形式是短横,占一个字的位置,印刷行业叫一字线,它还有另外两种形式,就是半字线(-)和波浪线(~)。连接号和破折号不同,不要相混。破折号是一长横,占两个字的位置。 一字线连接号连接词语,构成复合结构。例如:在我国大力发展第三产业的问题,以经得到经济——社会发展战略的决策人员和研究人员的重视。 一字线连接号还可以连接名词,表示起始和走向。例如:马尼拉-广州-北京行线八月一日首次通行 半字线连接号连接号码、代号,包括产品型号、序次号、门牌号、电话号、帐号等。前后多是隶属关系,可以读“杠”。例如:CH-53E是在CH-53D的基础上重新设计的更大型的重型起重直升机,公司编号S-80,绰号“超种马” 半字号连接号连接外国人的复姓或双名,例如:让-皮埃尔·佩兰 波纹线连接号连接数字表示数值的范围,例如:芽虫可用40%乐果乳剂800~1000倍液防治 一字线连接号也可以连接相关数字,例如:鲁迅(1881-1936) 半字号连接号连接阿拉伯数字表示年、月、日。这是国际标准化组织推荐的形式。例如:1993-05-04(1993年5月4日) 一、使用场合 1.一字线 一字线主要用于2个或2个以上名词或时间之间的连接,表示走向、起止和递进关系。(1)连接相关的方位名词,构成一个整体,表示走向关系。 [例1] 四川省达州市位于秦巴山系沿东北—西南方向向四川盆地过渡的地理阶梯之中。[例2] 我国的秦岭一淮北地区属于温带季风气候。 (2)连接相关的地点,表示空间或地理位置上的起止关系。 [例3] 2007年8月10日,深圳—重庆—拉萨航线首航成功。 再如:北京—天津高速公路;上海—杭州的D651次动车组列车。 (3)连接相关的时间,表示某一时间段的起止关系。 [例4] 20世纪80—90年代,中国东南沿海地区出现了“民工潮”现象。 再如:2000—2006年;2007年1—5月;2008年3月5—17日;上午8:00—12:00。(4)用于序数之间,表示起止关系。

浅谈公文标题中方案名顿括引等标点符的使用

浅谈公文标题中书名号、顿号、括号、引号等标点符号的使用 标题是公文的重要组成要素,是公文阅读者最先接触的部分。为确保公文阅读者能够准确理解公文所要表达的含义,应当规范制作公文的标题。要保证公文标题的规范化,就必须规范标题中标点符号的用法。《中国共产党机关公文处理条例》对公文标题使用标点符号没有作明确的规定,但《国家行政机关公文处理办法》则规定:“公文标题中除法规、规章名称加书名号外,一般不用标点符号。”此规定主要是为了保证公文标题的简洁,便于对公文的阅读、理解和处理。但是,应当注意规定中的“一般”二字,对这个要求的理解不能绝对化。否则,就会出现因为省略标题中不该省略的标点符号而造成理解上的困难。公文标题中究竟用不用标点符号,主要应看能否更好地揭示公文的中心内容。由于目前对公文标题中如何规范使用标点符号尚没有统一的规定,许多公文处理人员在实际操作中存在诸多不规范的地方,因此,对公文标题中标点符号的使用进行规范非常必要。 一、书名号的使用 在公文标题中,书名号使用最为广泛,也是惟一明文规定可以使用的标点符号。但有一点需要加以说明,这就是法规、规章名称之外是否可以使用书名号的问题。《国家行政机关公文处理办法》规定“公文标题中除法规、规章名称加书名号外,一般不用标点符号”,这个表述并未排除其他情况下也可使用书名号的可能性。除法规、规章名称外,在公文标题中出现书名、篇名、报纸名、刊物名时,也应当使用书名号。如在《×××关于做好〈××日报〉发行工作的通知》中,将“××日报”外的书名号去掉显然不妥。 二、顿号的使用

顿号用于句子内部并列词语之间的停顿。顿号在公文标题中主要用于两种地方。一是在出现多个发文机关时。在公文正文之上的标题中,多个发文机关名称的并列可以空格标示;但在正文之中被引用的公文标题,多个发文机关名称之间应该标上顿号。二是在发文事由中出现并列的词或短语时,可以视情况而定。为了作到公文标题的简洁,能不用顿号的尽量不用。有三种情况可以变通:第一,在只有两个并列词或短语时,它们之间可以用“和”等并列连词代替顿号;但如果出现第三个或三个以上并列词语,则应该使用顿号,如《国务院办公厅关于印发〈重新组建仲裁机构方案〉、〈仲裁委员会登记暂行办法〉、〈仲裁委员会收费办法〉的通知》。第二,对意思较为接近的并列词或词组,如果连用时中间不加顿号不会引起误解,可以省去顿号,如《中国银行业监督管理委员会关于加强元旦春节期间安全保卫工作的通知》,“元旦”和“春节”之间可以不加顿号。第三,在较长的标题中,可以通过换行的方式省去顿号,但前提是在排版时要做到正确换行,不要引起误解或歧义。 三、括号的使用 在公文标题中使用括号,主要用于解释或补充说明。 除上述几类常用的标点号外,还有一些不常用但偶尔见到的,如连接号、逗号、间隔号等。此外,公文处理人员还要注意在一个标题中使用多种标点符号的情况,要在尽量保持标题简洁的同时,注意标题表达意思的准确,不能随意省去标点符号。

标点符号:着重号、连接号 教学设计(人教版高三)

标点符号:着重号、连接号教学设计(人教版 高三) 一、着重号 (一)着重号的基本用法 提示读者特别注意的字、词、句,用着重号标示。示例:说“这个人说的是北方话”,意思是他说的是一种北方话,例如天津人和汉口人都是说的北方话,可是是两种北方话。 (二)着重号使用常见差错 1.:该用引号的地方却用了着重号。要注意着重号:和引号的不同,引号是用来标明着重论述的对象。如: *知已知彼是战争认识的主要法则,是“知胜”和“制胜”的认识基础。(着重号应改作:引号) *连词因为通常用在句子开头,后面用所以。(着重号应改作引号) 2.:滥用着重号。着重号要在十分必要时才用,并不是语气或语义一加重就用着重号。一段或一篇文字里加着重号的地方过多,就无所谓重点了。如:

*大家发现,尽管他说这些话时非常:真诚、自然、优雅,但听他这些话的人却大多显出迷惑不解乃至不安的神色。(应去掉着重号) *孩子自私心是:否强烈,主要取决于父母的培育方式和父母对孩子的态度。(应去掉着重号) 二、连接号 (一)连接号的基本用法 1.:表示连接。连接相关的汉字词、外文符号和数字,构成一个意义单位,中间用连接号。 (1)连接两个中文名词,构成一个:意义单位。示例:原子-分子论‖物理-化学作用‖氧化-还原反应‖焦耳-楞次定律‖万斯-欧文计划‖赤霉素-丙酮溶液‖煤-油燃料‖成型-充填-:封口设备‖狐茅-禾草-苔草群落‖经济-社会发展战略:‖芬兰-中国协会‖一汽-大众公司。 (2)连接外文符号,构成一个意义单位(应用半字线)。示例:Pb-Ag-Cu三元系合金。 (3)有机化学名词(规定用半字线)。示例:d-葡萄糖‖a-氨基丁酸‖1,3-二溴丙烷‖3-羟基丙酸。 (4)连接汉字、外文字母、阿拉伯数字,组成产品型号(可以用半字线)。示例:东方红-75型拖拉机‖MD-82客机‖大肠杆菌-K12‖ZLO-2A型冲天炉‖苏-27K型舰载战斗机

符号用法说明

符号用法说明 句号①。 1.用于陈述句的末尾。北京是中华人民共和国的首都。 2.用于语气舒缓的祈使句末尾。请您稍等一下。 问号? 1.用于疑问句的末尾。他叫什么名字?2.用于反问句的末尾。难道你不了解我吗? 叹号? 1.用于感叹句的末尾。为祖国的繁荣昌盛而奋斗? 2.用于语气强烈的祈使句末尾。停止射击? 3.用于语气强烈的反问句末尾。我哪里比得上他呀? 逗号, 1.句子内部主语与谓语乊间如需停顿,用逗号。我们看得见的星星,绝大多数是恒星。 2.句子内部动词与宾语乊间如需停顿,用逗号。应该看到,科学需要一个人贡献出毕生的精力。 3.句子内部状语后边如需停顿,用逗号。对于这个城市,他幵不觉得陌生。 4.复句内各分句乊间的停顿,除了有时要用分号外,都要用逗号。据说苏州园林有一百多处,我到过的不过十多处。

顿号、用于句子内部幵列词语乊间的停顿。正方形是四边相等、四角均为直角的四边形。 分号②; 1.用于复句内部幵列分句乊间的停顿。语言,人们用来抒情达意;文字,人们用来记言记事。2.用于分行列举的各项乊间。中华人民共和国行政区域划分如下: 1、全国分为省、自治区、直辖市。 2、省、自治区分为自治州、县、自治县、市。 3、县、自治县分为乡、民族乡、镇。 冒号: 1.用于称呼语后边,表示提起下文。同志们,朋友们:现在开会了…… 2.用于?说、想、是、证明、宣布、指出、透露、例如、如下”等词语后边,提起下文。他十分惊讶地说:?啊,原来是你?” 3.用于总说性话语的后边,表示引起下文的分说。北京紫禁城有四座城门:武门、神武门、东华门、西华门。 4.用于需要解释的词语后边,表示引出解释或说明。外文图书展销会 日期:10月20日至于11月10日

连接号的正确使用

连接号的正确使用 连接号是出版物中,特别是科技图书中经常使用的一类标点符号。国家标准《标点符号用法》(GB/T15834—1995)把连接号分为一字线(—)、半字线(-)、浪纹线(~)和长横线(——)4种形式,并列举了连接号的4种用法。但标准没有具体说明何种情况下使用哪一种形式。 连接号的4种形式在使用上有很大的区别。在很多出版物中,甚至在一些国家标准中,对连接号都有使用不当或错误的地方。本文现就连接号4种形式的正确使用作以下探讨。 一、各种形式连接号的使用场合 1.一字线的使用场合 一字线主要用于2个或2个以上名词或时间之间的连接,表示走向、起止和递进关系。 (1)连接相关的方位名词,构成一个整体,表示走向关系。 [例1] 四川省达州市位于秦巴山系沿东北—西南方向向四川盆地过渡的地理阶梯之中。 [例2] 我国的秦岭一淮北地区属于温带季风气候。 (2)连接相关的地点,表示空间或地理位置上的起止关系。 [例3] 2007年8月10日,深圳—重庆—拉萨航线首航成功。 再如:北京—天津高速公路;上海—杭州的D651次动车组列车。 (3)连接相关的时间,表示某一时间段的起止关系。 [例4] 20世纪80—90年代,中国东南沿海地区出现了“民工潮”现象。 再如:2000—2006年;2007年1—5月;2008年3月5—17日;上午8:00—12:00。 (4)用于序数之间,表示起止关系。 [例5] 2008年4月,出版社将出版《中国经济改革30年》(第1—13卷)。 再如:4—6年级;10一15行;35—37页。 (5)连接几个相关的项目,表示一种递进式关系。 [例6] 计算机经历了电子管计算机—晶体管计算机—集成电路计算机—大规模、超大规模集成电路计算机4个发展阶段。 [例7] 图书的间接销售主要是出版社—图书批发商—零售书店—读者这种形式。 上述的第(1)—(5)种用法中,一字线都有“至”(到)的意思,用“至”字替代,不影响句子意思的表达。 (6)其他固定用法。 ①用在标准代号年份之前。如:GB3102.11—93;GB/T16519—1996。 ②在化学类图书中用于表示化学键。如:—O—O—;—CN。 ③用于科技书刊的图注。如:1—2004年销售曲线;2—2005年销售曲线。 2.半字线的使用场合 半字线主要用于连接若干相关的词语或阿拉伯数字、字母等,构成一个具有特定意义的词组或代号。半字线没有任何字面意义,仅是前后两者之间的一种间隔关系。 (1)用于几个并列的人名之间,构成一个复合名词。如:焦耳-楞次定律;西蒙-舒斯特公司的教育出版部;任一洛二氏溶液。 (2)用于连接几个具并列关系的相关词语之间,构成复合词组。如:应力-应变曲线;总产量-平均产量-边际产量曲线图。 (3)用于插图、表格、公式等的编号的中间。如:图2-11;表3-5;式(5-13)。 (4)用于相关的字母、阿拉伯数字等之间,表示产品的型号。如:SDY-1A;DW-5725B-7D。 (5)用于国际标准书号、国际标准连续出版物号、国内统一连续出版物号代码之间。如:ISBN928-7-5624-3868-6;ISSN 1003-6687;CN 11-00790

着重号、连接号的正确使用-知识详解

着重号、连接号的正确使用-知识详解 一、着重号 (一)着重号的基本用法 提示读者特别注意的字、词、句,用着重号标示。示例: 说“这个人说的是北方话”,意思是他说的是一种北方话,例如天津人和汉口人都是说的北方话,可是是两种北方话。 (二)着重号使用常见差错 1. 该用引号的地方却用了着重号。要注意着重号和引号的不同,引号是用来标明着重论述的对象。如: *知已知彼是战争认识的主要法则,是“知胜”和“制胜”的认识基础。(着重号应改作引号) *连词因为通常用在句子开头,后面用所以。(着重号应改作引号) 2. 滥用着重号。着重号要在十分必要时才用,并不是语气或语义一加重就用着重号。一段或一篇文字里加着重号的地方过多,就无所谓重点了。如: *大家发现,尽管他说这些话时非常真诚、自然、优雅,但听他这些话的人却大多显出迷惑不解乃至不安的神色。(应去掉着重号) *孩子自私心是否强烈,主要取决于父母的培育方式和父母对孩子的态度。(应去掉着重号) 二、连接号 (一)连接号的基本用法 1. 表示连接。连接相关的汉字词、外文符号和数字,构成一个意义单位,中间用连接号。 (1)连接两个中文名词,构成一个意义单位。示例:原子—分子论‖物理—化学作用‖氧化—还原反应‖焦耳—楞次定律‖万斯—欧文计划‖赤霉素—丙酮溶液‖煤—油燃料‖成型—充填—封口设备‖狐茅—禾草—苔草群落‖经济—社会发展战略‖芬兰—中国协会‖一汽—大众公司。 (2)连接外文符号,构成一个意义单位(应用半字线)。示例:Pb-Ag-Cu三元系合金。 (3)有机化学名词(规定用半字线)。示例:d-葡萄糖‖a-氨基丁酸‖1,3-二溴丙烷‖3-羟基丙酸。 (4)连接汉字、外文字母、阿拉伯数字,组成产品型号(可以用半字线)。示例:东方红-75型拖拉机‖MD-82客机‖大肠杆菌-K12‖ZLO-2A型冲天炉‖苏-27K型舰载战斗机

标点符号的作用及用法

(一)标点符号的性质和作用 标点符号简称标点,是辅助文字记录语言的符号,是现代书面语里有机的部分。书面语如果不用标点,让人看起来会很吃力;如果用错了标点,还会造成理解上的困难。 标点符号的作用,大体上说,有三个方面:第一,表示停顿;第二,表示语气,标明句子是陈述语气,还是疑问语气,还是感叹语气;第三,标示句子中某些词句的性质。 1951年9月,中央人民政府出版总署公布了《标点符号用法》。这是我国政府公布的第二套标点符号。从50年代到80年代,汉语书面语发生了许多变化,文稿和出版物由直排改为横排,有些标点的用法也有了改变。1990年3月,国家语言文字工作委员会和新闻出版署联合发布了修订后的《标点符号用法》。这次修订主要体现在五个方面:(一)变直行用的标点符号为横行用的标点符号;(二)修订了部分标点符号的定义;(三)更换了例句;(四)简化了说明;(五)增加了连接号和间隔号。考虑到标点符号用法的社会影响较大,1994年,在国家技术监督局的提议下,《标点符号用法》改制为国家标准(GB/T 15834—1995),于1995年12月13日发布。 书面语言要正确使用标点符号,避免差错。标点的差错无非是:第一,不应该用标点的地方用了标点;第二,应该用标点的地方没有用标点;第三,应该用那种标点而用了这种标点;第四,标点应该放在那儿而放到了这儿。 为了学会正确使用标点符号,大家要学习一些语法知识,了解语言的结构规律,掌握组词造句的正确方法,这样也便于读懂讲解标点符号用法的书。 (二)标点符号的种类 国家标准《标点符号用法》中共有常用的标点符号16种,分点号和标号两大类。点号7种,标号9种。点号又分句中点号(逗号、顿号、分号、冒号,4种)和句末点号(句号、问号、叹号,3种)。标号包括:引号、括号、破折号、省略号、着重号、连接号、间隔号、书名号、专名号 二、句号 (一)句号的基本用法 陈述句末尾用句号。示例: ⑴中国是世界上历史最悠久的国家之一。 ⑵你明天在家休息休息吧。 ⑶他问你什么时候出发。

标点符号使用方法大全

标点符号使用方法大全

4.眼看你们的身子一天比一天衰弱,只要哪一天吃不上东西,说不定就会起不来。(小学《语文》第十一册《金色的鱼钩》) 例1非常简单,讲太阳给人们的感觉,是一个完整的句子,用句号。例2是一个较长的句子,它用四个“有的”把几种池底石笋的形象连在一块,句末用句号标示。例3是个长句子,实际是并列的三句话,讲了漓江水的三个特点:静、清、绿。因为三个句子作用相同、形式一样,联系紧密,放在一个大的句子中,中间用分号隔开。例4是一个带有关联词语的句子,“只要……就……”是连接构句的纽带,所以仍算为一个句子。 在阅读过程中,句号标志着停顿较大,即停顿的时间较长,例2例4中的逗号和例3中的分号,它们所标志的停顿时间都不能超过句号。 我们再看: 5.今天星期三。 6.昨天晴天。 7.随手关门。 这三个例句乍看上去都不像是个完整的句子,不符合我们平常认识的“谁(或什么)干什么(或怎么样)”的构句模式,但仔细一想,它们都表达了一个完整的意思,它们是句子的特殊形式,所以都使用句号。 从以上例句可以看出:用不用句号,关键不是看语言的长短,而是要看语言有没有表达一个完整的意思,能不能构成一个完整的句子。有的虽然只是一个词,但却能表达一个完整的意思,这个词就构成了一个句子。例如: 8.走。 9.没有。 有的虽然由多个词构成,但并没有表达一个完整的意思,按句子结构的要求,它只是句子的一个部件(又叫成分),那就不能算一个句子。例如: 10.大的小的、方的圆的、在阳光下闪着灿烂光辉的五彩池 不是句子,就绝不能用句号。完整的句子是不是就可以用句号呢?不一定,还要看这个句子的语气。句号适应于陈述语气、语调平缓的句子,语气很重的疑问句等就不能使用句号。如: 11.这是你的面包? 12.李黑,把枪放下! 这两个句子如果都换用句号,那么例11就不是问话了,而是告诉你“这面包是你的”,例12就不是命令的语气,而是向人陈述“李黑把枪放到地上”这个动作了。 (二)平时我们写作文,对句号的使用存在三种不正确的现象。

2016年高考语文标点符号的正确使用着重号、连接号素材

着重号、连接号 一、着重号 (一)着重号的基本用法 提示读者特别注意的字、词、句,用着重号标示。示例: 说“这个人说的是北方话”,意思是他说的是一种北方话,例如天津人和汉口人都是说的北方话,可是是两种北方话。 (二)着重号使用常见差错 1. 该用引号的地方却用了着重号。要注意着重号和引号的不同,引号是用来标明着重论述的对象。如: *知已知彼是战争认识的主要法则,是“知胜”和“制胜”的认识基础。(着重号应改作引号) *连词因为通常用在句子开头,后面用所以。(着重号应改作引号) 2. 滥用着重号。着重号要在十分必要时才用,并不是语气或语义一加重就用着重号。一段或一篇文字里加着重号的地方过多,就无所谓重点了。如: *大家发现,尽管他说这些话时非常真诚、自然、优雅,但听他这些话的人却大多显出迷惑不解乃至不安的神色。(应去掉着重号) *孩子自私心是否强烈,主要取决于父母的培育方式和父母对孩子的态度。(应去掉着重号) 二、连接号 (一)连接号的基本用法 1. 表示连接。连接相关的汉字词、外文符号和数字,构成一个意义单位,中间用连接号。

(1)连接两个中文名词,构成一个意义单位。示例:原子—分子论‖物理—化学作用‖氧化—还原反应‖焦耳—楞次定律‖万斯—欧文计划‖赤霉素—丙酮溶液‖煤—油燃料‖成型—充填—封口设备‖狐茅—禾草—苔草群落‖经济—社会发展战略‖芬兰—中国协会‖一汽—大众公司。 (2)连接外文符号,构成一个意义单位(应用半字线)。示例:Pb-Ag-Cu三元系合金。 (3)有机化学名词(规定用半字线)。示例:d-葡萄糖‖a-氨基丁酸‖1,3-二溴丙烷‖3-羟基丙酸。 (4)连接汉字、外文字母、阿拉伯数字,组成产品型号(可以用半字线)。示例:东方红-75型拖拉机‖MD-82客机‖大肠杆菌-K12‖ZLO-2A型冲天炉‖苏-27K型舰载战斗机 2. 表示起止。连接相关的时间、方位、数字、量值,中间用连接号。 (1)连接数目,表示数目(生卒日期、量值等)的起止(科技界习惯用浪纹)。示例:孙文(1866—1925)‖200—300千瓦‖20%—30%‖15—30℃‖-40 — -30℃‖1997—1998年‖1997年—1998年‖40%乐果乳剂800—1000倍液。 (2)连接地点名词,表示地点的起止(不要用浪纹)。示例:北京—上海特别快车‖北京—旧金山—纽约航班‖秦岭—淮河以北地区。 3. 表示流程。连接几个相关项目表示事物递进式发展,中间用连接号,也可以用两字线或者箭头。不过箭头不属于标点。示例: ⑴人类的发展可以分为古猿—猿人—古人—新人这四个阶段。 ⑵在一九四二年,我们曾经把解决人民内部矛盾的这种民主的方法,具体化为一个公式,叫做“团结——批评——团结”。 ⑶邮局汇兑的基本过程:汇款人→收汇局→兑付局→收款人。 (二)提示 1. 连接号的常用形式为一字线“—”,占一个汉字位置。此外还有半字线“—”和浪纹“~”。 2. 中文半字线连接号与西文连字符(hyphen)长短不同,不可混用。

浅谈图形的符号性

浅谈图形的符号性 图形作为一种艺术表达手段,具有交流的功能与目的,同时具备自己独特的语法形式、语法内涵、语言手段和语言环境。符号性是把原本具有自然属性的事物用图形表现,脱离它原有属性的限制,将其理想化并为它赋予特定寓意产生出新的概念。在设计中对图形符号的正确解读,是对设计的衡量标准。设计应该选择并合理恰当的利用符号语言,使画面词汇达到丰富的状态。 标签:读图时代图形语言符号性 今天是一个视觉传媒高度发展的时代,“读图时代”一词不断地被提及。设计借用图形的基本功能来传递信息,通过设计者的创造性思维和设计能力,使信息借助视觉图形更有效的传达。随着人类文明的发展,图形传达被大量应用在绘画、书籍装帧、商业、产品包装设计、海报招贴等艺术形式中,图形的形式与构成元素在不断丰富更新,各种不同艺术形式相互交融、电脑技术飞速发展,使图形表现和传达更为丰富更具有个性化。人类日益提高的物质和精神需求对图形的表现形式提出了时代的要求,它应该具备更高的艺术诉求形态和多样性的表现手法,这些就需要通过更为丰富的技术手段和多维的设计元素来实现。 图形作为一种艺术表达手段,必须具备交流的功能目的,具备自己独特的语法形式,语法内涵,语言手段和独特语言环境。 图形语言的产生,可以是自然界自然物象的规律特征,可以是其他语言形式的转化,可以是来自架上艺术的借鉴。图形是具备无障碍沟通性的世界性符号,越具有世界共通性的图形特征越能体现出本土文化特色。 1 图形符号的认知性 图形元素作为一种艺术表现形式,在艺术设计中作为表述工具进行表达。它具备符号的属性,在观者对图形符号直接认知的基础上利用图形与其语境之间的关系,延伸出图形符号的第二层含义体现出一些潜藏的、隐形的信息。 图形的象征符号是把原本具有自然属性的事物用图形表现,脱离它原有属性的限制,将其理想化并为它赋予特定寓意产生出新的概念。现实世界中的事物都可以转化为一些特定的图形,将具象转化为抽象并且借助符号象征一定涵义。这些符号涵义产生于人们与现实事物之间的利害关系,或者形成于对现实事物在实践中产生的心里感受。这种情感关系与心理感受,能够在时间的延续中,逐渐失去原有的本质而被“某些观念”代替从而定义为符号的涵义并且由初始的模糊逐渐稳定。这些演变过来的具有着某些历史观念意义或者传统象征的符号,是经过大多数人情感认同的结果,并与之心理息息相关。它们具有普遍、普及、大众认知的可识别性。将它的“某些观念”注入一些相关可识别符号中使之产生的新的涵义这些象征图形符号除了传递出准确信息延续着某种情感外还具备着饱满的艺术形态,成为现代艺术中备受青睐的一组重要元素。

连接号用法及常见差错辨析

连接号用法及常见差错辨析 (一)连接号的基本用法 1. 表示连接。连接相关的汉字词、外文符号和数字,构成一个意义单位,中间用连接号。 (1)连接两个中文名词,构成一个意义单位。示例:原子—分子论‖物理—化学作用‖氧化—还原反应‖焦耳—楞次定律‖万斯—欧文计划‖赤霉素—丙酮溶液‖煤—油燃料‖成型—充填—封口设备‖狐茅—禾草—苔草群落‖经济—社会发展战略‖芬兰—中国协会‖一汽—大众公司。 (2)连接外文符号,构成一个意义单位(应用半字线)。示例:Pb-Ag-Cu三元系合金。 (3)有机化学名词(规定用半字线)。示例:d-葡萄糖‖a-氨基丁酸‖1,3-二溴丙烷‖3-羟基丙酸。 (4)连接汉字、外文字母、阿拉伯数字,组成产品型号(可以用半字线)。示例:东方红-75型拖拉机‖MD-82客机‖大肠杆菌-K12‖ZLO-2A 型冲天炉‖苏-27K型舰载战斗机 2. 表示起止。连接相关的时间、方位、数字、量值,中间用连接号。(1)连接数目,表示数目(生卒日期、量值等)的起止(科技界习惯用浪纹)。示例:孙文(1866—1925)‖200—300千瓦‖20%—30%‖15—30℃‖-40 — -30℃‖1997—1998年‖1997年—1998年‖40%乐果乳剂800—1000倍液。 (2)连接地点名词,表示地点的起止(不要用浪纹)。示例:北京—上海特别快车‖北京—旧金山—纽约航班‖秦岭—淮河以北地区。 3. 表示流程。连接几个相关项目表示事物递进式发展,中间用连接号,也可以用两字线或者箭头。不过箭头不属于标点。示例: ⑴人类的发展可以分为古猿—猿人—古人—新人这四个阶段。 ⑵在一九四二年,我们曾经把解决人民内部矛盾的这种民主的方法,具体化为一个公式,叫做“团结——批评——团结”。 ⑶邮局汇兑的基本过程:汇款人→收汇局→兑付局→收款人。 (二)提示 1. 连接号的常用形式为一字线“—”,占一个汉字位置。此外还有半字线“-”和浪纹“~”。 2. 中文半字线连接号与西文连字符(hyphen)长短不同,不可混用。 3. 用于表示时间、数字、量值的起止,一字线与浪纹的功能相同,出版物可选择其中一种。科技文章常出现负号“-”,为避免与一字线勾

浅谈连接符号的用法

浅谈连接符号的用法 连接号是出版物中,特别是科技图书中经常使用的一类标点符号。国家标准《标点符号用法》(GB/T15834—1995)把连接号分为一字线(—)、半字线(-)、浪纹线(~)和长横线(——)4种形式,并列举了连接号的4种用法。但标准没有具体说明何种情况下使用哪一种形式。 连接号的4种形式在使用上有很大的区别。在很多出版物中,甚至在一些国家标准中,对连接号都有使用不当或错误的地方。本文现就连接号4种形式的正确使用作以下探讨。一、一字线的使用规范 一字线主要用于2个或2个以上名词或时间之间的连接,表示走向、起止和递进关系。 1.连接两个相关的名词构成一个意义单位,用一字线。 【例】原子一分子论,中国一芬兰协会。(也可以用半字线,但不要用长横)(统一用“—”字线) 2.连接相关的地点、时间表示走向或起起止。表示空间或地理位置上的起止关系。 【例】四川省达州市位于秦巴山系沿东北—西南方向向四川盆地过渡的地理阶梯之中。北京—天津高速公路;上海—杭州的D651次动车组列车。我国的秦岭一淮北地区属于温带季风气候。 3.连接相关的时间,表示某一时间段的起止关系。 【例】 20世纪80—90年代,中国东南沿海地区出现了“民工潮”现象。 再如:2000—2006年;2007年1—5月;2008年3月5—17日;上午8:OO—12:OO。 4.用于序数之间,表示起止关系。 【例】2008年4月,出版社将出版《中国经济改革30年》(第1—13卷)。再如:4—6年级;10一15行;35—37页。 5.连接几个相关的项目,表示一种递进式关系。 【例】计算机经历了电子管计算机—晶体管计算机—集成电路计算机—大规模、超大规模集成电路计算机4个发展阶段。 一字线有“至”(到)的意思,用“至”字替代,在不影响意思表达的时候也可以互换。 6. 表示一个人的生卒年统一用“—”字线, 【例】鲁迅(1881—1936),(前者也可以用长横,后者也可以用浪纹,但不要用半字线)(表示一个人的生卒年统一用“—”字线) 7.其他固定用法。 (1)用在标准代号年份之前。如:GB3102.11—93;GB/T16519—1996。 (2)在化学类图书中用于表示化学键。如:—O—O—;—CN。 (3)用于科技书刊的图注。如:1—2004年销售曲线;2—2005年销售曲线。 二、半字线的使用规范 半字线主要用于连接若干相关的词语或阿拉伯数字、字母等,构成一个具有特定意义的词组或代号。半字线没有任何字面意义,仅是前后两者之间的一种间隔关系。 1.用于几个并列的人名之间,构成一个复合名词。 【例】焦耳-楞次定律;西蒙-舒斯特公司的教育出版部;任-洛二氏溶液。

标点符号的作用及用法大全

标点符号的性质和作用 一、标点符号的种类、作用: 种类:16种,分点号和标号两大类。点号7种,标号9种。点号又分句中点号(逗号、顿号、分号、冒号,4种)和句末点号(句号、问号、叹号,3种)。标号包括:引号、括号、破折号、省略号、着重号、连接号、间隔号、书名号、专名号 作用:第一,表示停顿; 第二,表示语气,标明句子是陈述语气、疑问语气,还是感叹语气; 第三,标示句子中某些词句的性质。 二、点号 (一)问号 1. 疑问句末尾用问号。 2. 反问句末尾一般用问号。 注意: 1. 选择问句问号的位置。一般的情况是,选择项之间用逗号,问号用在最后一个选择项之后。示例: 是英雄造时势,还是时势造英雄? 2. 选择问句如果要强调每个选择项的独立性,可以在每个选择项后都用问号。示例: 还是历来惯了,不以为非呢?还是丧了良心,明知故犯呢? (二)叹号 1. 感叹句末尾用叹号。 2. 语气强烈的祈使句末尾用叹号。如:你不要再废话了! 3. 语气强烈的反问句末尾用叹号。示例: 你怎么能这样对待一个不懂事的孩子呢! 4. 标语口号末尾,一般用叹号。示例:全国各民族大团结万岁! (二)提示 1. 在表示极其强烈的感叹时,可以使用“!!”及“!!!”这样的叹号叠用形式。但是请注意:(1)要得体,不要滥用。(2)要使用半角标点,让它们挨在一起。示例: 宁为玉碎,不为瓦全。她要揭露!要控诉!!要以死作最后的抗争!!! 2. 带有强烈感情的反问句,允许问号和叹号并用。但是请注意:(1)要得体,不要滥用。(2)要使用半角标点,让它们挨在一起。示例: “什么?”男人强烈抗议道,“你以为我会随便退出娱乐圈吗?!” 3. 带有惊异语气的疑问句,允许问号和叹号并用。示例: 周朴园:鲁大海,你现在没有资格和我说话——矿上已经把你开除了。 鲁大海:开除了?! 4. 像上面问号和叹号并用的形式,因为问多于叹,所以建议采用“?!”式,而不采用“!?”式。

标点符号使用方法大全

《标点符号使用方法大全》,现在的小学生,不加标点或者乱点标点的情况时有发生,今天,我们把有关标 点符号的知识分享给大家,请有孩子的朋友收藏下来。 一、标点符号歌: 句号(。)是个小圆点,用它表示说话完。 逗号(,)小点带尾巴,句内停顿要用它。 顿号(、)像个芝麻点,并列词语点中间。 分号(;)两点拖条尾,并列分句中间点。 冒号(:)小小两圆点,要说话儿写后边。 问号(?)好像耳朵样,表示一句问话完。 叹号(!)像个小炸弹,表示惊喜和感叹。 引号(“”)好像小蝌蚪,内放引文或对话。 话里套话分单双,里单外双要记牢。 省略号(……)六个点,表示意思还没完。 破折号(——)短横线,表示解说、话题转。 书名号(《》)两头尖,书、刊名称放中间。 圆括号(),方括号[],注解文字放里边。 学标点,并不难,多看多练才熟练。 二、写作常用标点符号使用方法 一、基本定义 句子,前后都有停顿,并带有一定的句调,表示相对完整的意义。句子前后或中间的停顿,在口头语言中,表现出来就是时间间隔,在书面语言中,就用标点符号来表示。一般来说,汉语中的句子分以下几种: 陈述句:用来说明事实的句子。 祈使句:用来要求听话人做某件事情的句子。 疑问句:用来提出问题的句子。 感叹句:用来抒发某种强烈感情的句子。 复句、分句:意思上有密切联系的小句子组织在一起构成一个大句子。这样的大句子叫复句,复句中的每个小句子叫分句。 构成句子的语言单位是词语,即词和短语(词组)。词即最小的能独立运用的语言单位。短语,即由两个或两个以上的词按一定的语法规则组成的表达一定意义的语言单位,也叫词组。 标点符号是书面语言的有机组成部分,是书面语言不可缺少的辅助工具。它帮助人们确切地表达思想感情和理解书面语言。 二、用法简表名称符号用法说明举例 (一)句号。 1、用于陈述句的末尾。北京是中华人民共和国的首都。 2、用于语气舒缓的祈使句末尾。请您稍等一下。 (二)问号? 1、用于疑问句的末尾。他叫什么名字? 2、用于反问句的末尾。难道你不了解我吗? (三)感叹号! 1、用于感叹句的末尾。为祖国的繁荣昌盛而奋斗! 2、用于语气强烈的祈使句末尾。停止射击! 3、用于语气强烈的反问句末尾。我哪里比得上他呀! (四)逗号, 1、句子内部主语与谓语之间如需停顿,用逗号。我们看得见的星星,绝大多数是恒星。

浅议英语连字符连接的复合词

摘要:连字符在英语中的表达力很强,如果运用得当,可以精炼篇章语句,使得译文简洁达意。连字符复合词是一种极为活跃的构词法,是一种丰富多彩、富有无穷魅力的语言现象。连字符复合词之所以增加得如此迅猛,在于它的简便表现手法更符合现代英语日趋简化的趋势。此外,在一些中国特色常用词语的汉英翻译中,有时也会用英语连字符连接,熟练掌握这些特色词,能避免产生歧义,简化汉英翻译。因此,了解和熟练运用连字符复合词对于我们学习和使用英语是十分必要的。 关键词:英语连字符连接复合词连字符(hyphen )是英文中常见的一种标点符号,具有许多种作用,如用于词缀(或组合语素)与词根(或词)之间,避免单词在语义或在语音上发生混淆或用于分离,分解音节,单词移行等。它能把两个或两个以上的单词连接起来,构成新的形容词性合成词。本文仅简略地介绍它在复合词修饰语中的使用规则。 1.用连字符连接的常用的复合词修饰语的理解误区 在两个或多个单词组成复合词作修饰语的情况下,一般需要使用连字符以避免误解,除非是“名词—名词”或“副词—形容词”组合。如hot-water bottle 。如果没有连字符,那么这个词组也可以理解为“一个热的水瓶(A hot water bottle is a water bottle that is hot )”,而不是本来要表达的“一个用来装热水的瓶子(A hot-water bottle is a bottle for holding hot water )”。如果这个复合词放在被修饰词的后面,那么连字符的使用取决于该复合词是否为形容词。如American-football player 变为a player of American football 不需要使用连字符,因为复合词不作形容词;而left-handed catch 变为he took the catch left-handed 则依然使用连字符,因为复合词作形容词。 2.用英语连字符连接的常用的复合词修饰语的种类2.1在“名词—名词”组合的词中。 在“名词—名词”组合的复合词作为形容词时,一般不需要连字符,因为混淆的可能性很小。但是有时侯需要突出某些特定的成分或者修饰语,会用连字符来加以强调。 例如:Is the fare like a last resort for public-transport compa -nies ,or is raising fares a knee-jerk reaction to an increase in op -erational costs?(提高乘车费难道是公共交通公司最后的手段,或者是对承运成本增加的直接反馈?)这里的“public-trans -port ”和“knee-jerk ”就是这样的组合,前者是强调公共交通,后者则栩栩如生地突出了反馈的速度之快,很形象生动。比如:parent-child relationships 。 2.2在“名词—分词”组合的词组中。 在“名词—分词”组合的复合词修饰语中,一般是动宾的关系。前面的名词是后面动词的宾语,其作用也是起了突出强调的效果。 例如:These are value -for -money ice -cream moon cakes that kids will fancy.With 8flavors to choose from ,these tasty treats will keep the kids happy while the adults bond over a session of moon-gazing and tea-drinking.(这些是孩子们钟爱的物超所值的冰淇淋月饼。有8种口味可以选择。当大人们在赏月和饮茶的时候,这些美味的点心也能使孩子们感到高兴。)“value-for-money ”这个修饰语属于前面提到过的“名词—名词”组合, 它把“物超所值”这层意思浓缩得很好,一般来说,如果不用这个修饰语,我们会用一句定于从句来表达这层意思,如:These ice-cream moon cakes which have good quality but inexpensive prices.这样整个句群会显得很长,而名词—名词组合怎使句子 精简,表达生动。 同样的,“moon-gazing ”和“tea-drinking ”是“名词—动词现在时”组合的复合词修饰语,一般的正常语序是“gaze moon ”和“drink tea ”,但是这里是将动宾词组活用作名词,目的也是为了缩短句群。 再举一个例子:A way to build one could be buying into money-producing assets such as high dividend-yielding stocks.这里的“money-producing ”和“dividend-yielding ”的正常语序是“produce money ”和“yield dividend ”,但是这里就为把动宾词组转化成形容修饰语,使得英语表达方式多变,使句子显得优美流畅,避免繁复。 2.3在“名词—形容词”组合的词组中。 例如:Most pub grab foods are greasy.And the meals you ’ll tend to go for after a drinking session definitely not the most waist -line-friendly.(大部分酒吧的小食是比较油腻的。而畅饮结束后的餐食绝对是容易使人发胖的。)“waistline-friendly ”一词很形象生动地说明腰围要变粗,比起说“make people fat ”表达方式更婉转,词句变换方式更多样。类似的词组有:export-ori ented economy ,result -oriented boss ,market -driven education ,sales-based ,commission-based salary 。 另外一个例子:Chili curbs the appetite ,and this is why peo -ple in poorer countries make their food very hot-so they don ’t get hungry so soon.This would explain why South Indian food is spici -er than North Indian food ,and in other words ,people in South In -dian are more chili-tolerant.(由于辣椒能控制胃口,所以许多 贫困国家的人会习惯做比较辛辣的食物。这样一来他们不会很容易感到饥饿。这也同样可以解释为什么印度南部的食物要比印度北部的食物更加辣,换而言之,也可以说南印度的人更耐辣。)这里的“chili-tolerant ”非常简洁地表达耐辣度这个概念,“tolerant ”本身是忍受,“chili-tolerant ”也可以解释为be tolerant of chili 。 2.4在形容词性词组中。 2.4.1连字符还用来连接数字,如10-year-old boy (ten-year-old boy )。以文字形式拼写出来的分数作形容词时也使用连字符,如two-thirds majority ,但作名词时则不使用。如果使用国际单位符号(注意不是单位的名称)时则不使用连字符,如a 25kg ball (使用符号)与a roll of 35-millimetr film (不使用符号而是使用名称)。 如果“形容词—名词”在单独使用情况下为复数形式,在使用连字符时要变单数,如four days 与four-day week 。如果使用and ,or ,to 连接不同的、连续的、使用连字符的词修饰同一个单词,可以使用“悬垂”连字符,如nineteenth-century and twen -tieth-century 可写成nineteenth-and twentieth-century 。 2.4.2由形容词+(名词+ed )构成的合成形容词,如:a kind-hearted woman 一个心地善良的人 a simple-minded young man 一个头脑简单的年轻人a left-handed person 一个左撇子 a narrow-minded man 一个心胸狭窄的人an old-fashioned machine 一台老式机器 2.4.3由形容词或副词+分词构成的合成形容词,如:a good-looking boy 一个帅小伙a new-born baby 一个新生婴儿 a badly-lighted room 一间光线昏暗的房间 (天宝寰宇电子产品上海有限公司,上海 200131) 张 懿 浅议英语连字符连接的复合词 90